MANHATTAN, KAN. — K-State Extension agents, Kansas Wheat staff, certified crop advisers, growers and others took measurements in wheat fields across Kansas and reported findings via Zoom sessions during the first HRW Virtual Wheat Tour. Initial reports focused on north-central and northwest Kansas.

The calculated yield range in north-central Kansas was 25.6 to 59.4 bus per acre (bpa) with an average of 41.1 bpa. The yield range in northwest Kansas varied widely from 20 to 117 bpa with an average of 51.7 bpa. The averages compared with the US Department of Agriculture yield prediction for Kansas of 47 bpa.

K-State extension agent Romulo Lollato, an assistant professor of wheat and forages production at Kansas State University, gave virtual tour-takers a snapshot of the crop live from a Lane County, Kan., wheat field.

“The eastern portion of the region, Cloud County and Clay County, are in decent shape, have enough moisture and yields we measured there were consistently 50, 55 bpa,” he said. “As we headed west to Republic County we were still able to find some good yield potential. As we moved west to Smith County, Phillips County, that’s where we found some of those in the lower 20, 25 bpa range.”

Fields in the northern tier of Kansas County planted late after soybeans that had less time for development felt the freeze to a greater degree, he said. Further south in Rooks and Russell counties, wheat was in better shape. This is where a 72 bpa field was measured, Mr. Lollato said.

Drought stress was plainly evident in fields in Ellis and Phillips counties and parts west from there, he said.

“Development-wise, we’re ranging anywhere from the boot stage in the northern part of the state to flowering,” he said.

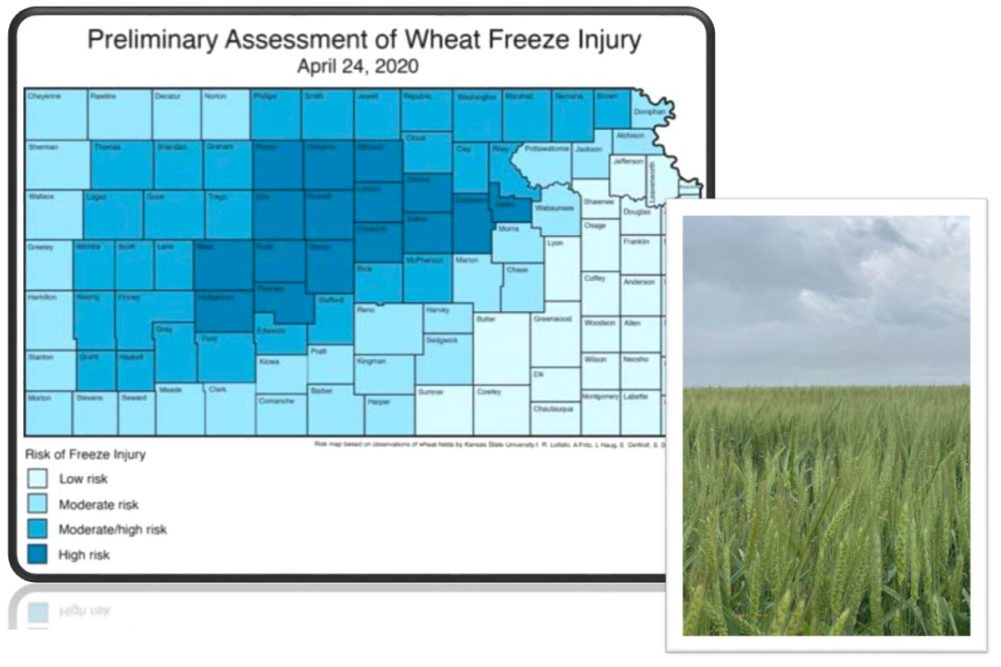

He said the consistent theme of visual inspections in north central Kansas was “drought and freeze symptoms in every single field. What does that look like? Sometimes the lower canopy is going to be very lush. You can see that there is going to be a lot of density of stems. But the upper canopy is much thinner. You don’t have the same number of stems that are going to produce a head on the upper canopy, mostly because they were terminated by the freeze back in April.”

Tan spot and septoria were the most prominent disease pressures noted in the region, Mr. Lollato said.

“As far as stripe rust goes, which is a big concern, we found it in four counties,” he said. “We didn’t find it in the flag leaf, more in the middle of the canopy. But it’s there, and it can be a threat coming up, especially because the crop there is still in the boot stage starting to head.”

Barley yellow dwarf was the main viral disease found in the region, he said, transmitted by the consistent aphid population found across the state after the freeze events in April.

“It’s now something that’s too widespread, but every now and then we’ll come across fields that have hot spots of barley yellow dwarf,” Mr. Lollato said.

Jeanne Falk Jones, a K-State multi-county agronomist covering Cheyenne, Sherman and Wallace counties, gave tour attendees an update from northwest Kansas, where “variability is the name of the game,” she said. That was evident in her photos showing both thin stands of drought-stressed wheat and lush, taller fields.

Crop appearance was influenced by field management prior to seeding the crop last fall. Growth prior to dormancy was limited and the root development was poor overall. Some growers indicated weed pressure sapped a considerable portion of the soil moisture in places, resulting in stands ranging from poor to excellent.

A freeze event April 2-3 left much of the crop with cosmetic damage in the form of leaf burn, but the growing point remained below the soil surface, which helped protect plants, Ms. Falk Jones said. When a second cold-temperature event began on Easter, the growing point was just below the soil surface to just above it. Three days of cold temperatures not only browned leaf tips but caused the loss of some tillers. But freeze damage differed by field, she said. Some photos displayed during the meeting showed brown tillers on the ground with new green growth rising from them.

“One farmer said it’s good that it’s growing, but we didn’t have the moisture to spare to regrow a bunch of leaf tissue,” she said. As a result, “we have some small tillers coming up that aren’t reproductive tillers that will add to our yields.”

That lack of moisture means part of the northwest Kansas crop was growing in drought-stressed areas without strong root systems below. Subsoil moisture was available 6 to 8 inches below the surface, but short roots weren’t reaching it, and remaining topsoil moisture was sapped by regrowth after the freeze, Ms. Falk Jones said. Some of the wheat was “kicked back into gear” by a mid-May rain that dropped up to 1½ inches of rain.

Drought conditions also have led to insect pressures, such as brown mites. Some aphids and their accompanying predators, ladybugs, also were spotted, she said. Wheat stem sawfly continued to be a discussion point in northwest Kansas, as some adult specimens have been collected in the region. But Ms. Falk Jones added than no physical damage from them had been recorded so far.

Mild disease pressure was noted from wheat streak mosaic, tan spots and stripe rust in northwest Kansas. Some weed pressure of the winter annual variety — mustards, downy brome and cheat — remained a concern, especially in areas of thin wheat stands.