MINNEAPOLIS — Buyers and sellers of such agricultural products as dried distiller’s grain and soybeans carried between continents on massive container vessels should expect little relief from high prices in 2022.

Nor should they expect much improvement in the upended global supply chain that has sent schedule reliability to an all-time low and doubled the average delay time for container ship arrivals at US ports backed up by short labor and equipment.

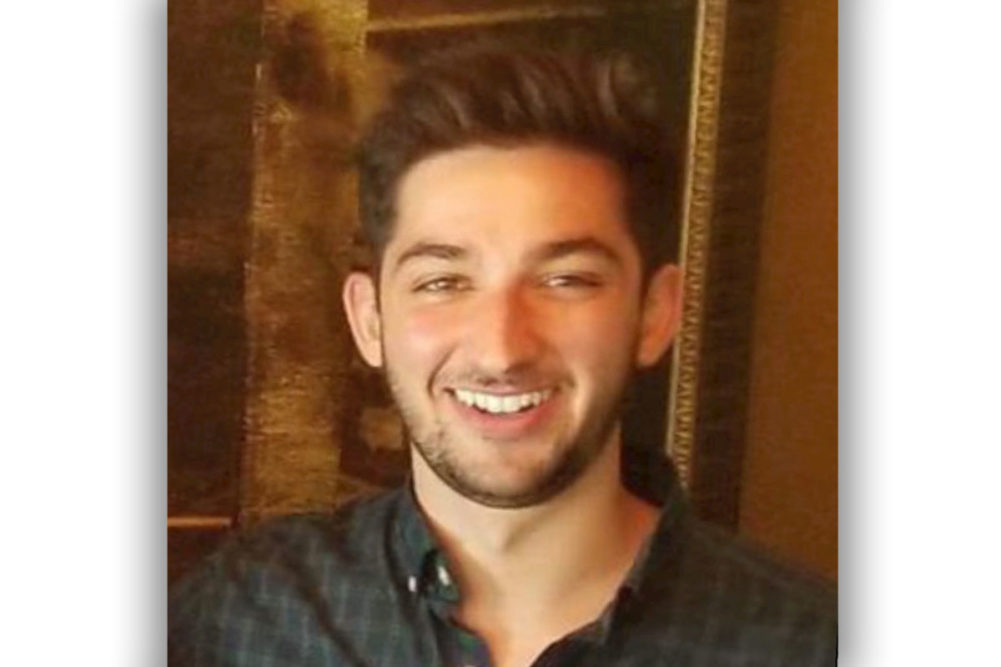

Those were key takeaways from Walter Lanza of Scoular, Omaha, Neb., during a breakout session on the effects of shipping disruption on US agriculture during the US Department of Agriculture’s 98th Agricultural Outlook Forum. As a commodity export trade manager, Mr. Lanza oversees international trade and supply chain for animal products spanning North America, South America, Europe, Africa and Asia.

Modern container ships are a relatively new development considering ships have taken to the seas for thousands of years, Mr. Lanza said. Transporting goods by ship was a time-consuming, complicated endeavor until Malcolm McLean designed and shipped the first containers from New Jersey to Houston in the 1950s. That began what would later be known as intermodal freight featuring shipping containers that can be lifted from ships and placed directly atop flat-bed railcars or on chassis hauled by trucks.

Loading costs using the new method dropped 97%, to 16¢ per ton from $6 per ton, enabling remarkable growth in trade between countries. Containers were among the factors that pushed global gross domestic product, which had been growing steadily in the 1950s, sharply higher after 1960. The resulting integration of the US economy into the global economic system was one of the most important developments of the 20th century. It allowed domestic firms to become true international companies and the world went from small manufacturers to bigger and then global companies in less than 50 years.

In that time, ships grew ever larger. There are ships in service today that can accommodate nearly 40,000 containers with a total value of over $1.2 billion. As freight became more efficient and ships got bigger, freight rates have been relatively steady to slightly weaker in the years 2005 to 2020.

“This low-freight environment was not good for the steamship lines,” Mr. Lanza said. “From 2008 to 2016 earnings were positive some years, but negative other years. It was not the most attractive industry to be a part of. The lack of sustainable profit triggered acceleration of industry consolidation. For the past 20 years, we’ve seen many names disappear and a lot has changed. The number of top steamship lines became more and more condensed.”

Ultimately, shipping companies settled into what is known as the big three of the seas: The 2M alliance of Maersk Line and Mediterranean Shipping Co.; the Ocean Alliance of Cosco, OCL, Evergreen and CMA; and The Alliance of Hapag-Lloyd, Yang Ming and ONE, the latter a recent consolidation of the top three Japanese carriers.

In January 2020, just before the COVID-19 pandemic went global, the market for shipping containers was so slow that 13% of the capacity was idled, 250 scheduled sailings were canceled for the April-June 2020 period and vessels were only running about half full. In March, when the United States went into lockdown mode, unemployment shot up overnight while the airline and hospitality sectors tanked. With folks stuck at home, many stimulus dollars went to home improvement and new furnishings, a key feature of the economic recovery.

“It is interesting to compare it with the 2008 recession where consumer spending dropped for everything, because more people were unemployed and were spending less,” Mr. Lanza said. “In 2020, while the service industry had a big drop, people started buying a lot more goods. You can see a drop in March 2020 for the sales-retail sector, but it recovered by July and continued to break the trend. All major retailers were posting milestones and records, including Target, Walmart and Amazon. Sales and revenue were the highest they’d ever seen, so the main thing they had to do was replenish inventories.”

That proved no easy task.

The massive uptick in demand decimated inventories and overwhelmed the supply chain. Container rates began to tick higher and did so consistently for 18 months. The rate between China and the United States went from around $1,500 per container to almost $15,000, and certainly affected some US agriculture exports. Even worse, some ships sailed empty, no longer interested in waiting in port for lower priced agriculture backhauls of products like DDGs and soybeans. Unsurprisingly, steamship lines saw record earnings in 2021 and unprecedented profitability. The industry has made twice as much in the first nine months of 2021 than in the previous 10 years combined, Mr. Lanza said.

Would more ships solve the problem? Not likely, he said, noting that it takes $200 million to $300 million and two to three years to build vessels of this size. More are being constructed but will only compound what is essentially an infrastructure problem.

“More vessels would simply be added to the interminable queues of vessels around the world waiting to unload,” Mr. Lanza said. “Around 12% of goal capacity has been absorbed due to delays, compared to the average of about 2%. There was a record-high 80-plus containers waiting to unload at LA-Long Beach in October of last year. This is probably several million containers or about $25 billion of cargo, which for comparison is higher than the GDP of some small countries such as Iceland.

“The ports already made a few changes to become more efficient. Some ports extended hours to 24/7 operations, but the problems go a bit deeper. There is a shortage of workers across the industry, including dockworkers, truckers and warehouse workers. After the port there is a lack of chassis and lack of drivers to pick them up at port. The same when they get to warehouses. They get behind because there are not enough workers to unload. The problem just gets bigger, like a snowball.”

Meanwhile reliability is at an all-time low, as well, he said, pointing to Sea Intelligence data measuring schedule reliability across 34 different trade lanes. Reliability is at around 35% to 40% today, considerably lower than the historical average of about 75%. Consequently, the average delay for arrival is now eight days compared with an average of four historically.

In the extremely tight US labor market, some reports have estimated the trucking shortage at about 80,000 drivers and projected that number to increase until about 2030. Fewer drivers results in reduced capacity and higher rates. That’s a pain point for all, but especially the agriculture sector, Mr. Lanza explained.

“In a world with finite resources, it is a challenge to compete with Walmart, Target and all the major retailers. Depending on what product retailers are moving, the total cargo value can go from a few hundred thousand dollars all the way up to a few million dollars. Compared to a load of soybeans, which is valued at about $15,000 today, the value of cargo is considered considerably lower.”

So, what does 2022 have in store?

For one thing, there aren’t any signals increased demand is abating or that the supply chain backups that changed the global economy and spurred inflation are improving. Bottlenecks due to a lack of chassis equipment for containers and labor shortages at ports and in the cabs of big rigs will continue. Container times in depots will continue to be high. While he doesn’t see much downside potential for freight rates, Mr. Lanza doesn’t see them soaring much higher.

As he sees it, the challenge for the industry is fourfold.

Clogged ports, a major limiting factor exacerbated when containers dwell on docks, might be addressed with pickup incentives that some steamship lines are offering. Dry ports further into the US interior could alleviate some pressure, as could making the ports more automated, like some European locations. Chassis, the metal beds with wheels that carry the containers, are in extremely short supply. The production of chassis should be incentivized and the cost of importing them reduced, he said.

Also key is warehouse capacity expansion and hiring more people to unload cargo. Industrial vacancies nationwide fell to a record low of about 3% in 2021, and the country’s largest and most important warehouse and distribution center in California had a vacancy rate of just 0.67% in the third quarter.

Finally, the labor problem, from port workers to warehouse workers to truck drivers, must be addressed.

“The shipping industry will have to adapt and create incentives and look elsewhere to try to fill open positions,” Mr. Lanza said. “None of the freight issues have an easy solution. We continue to see challenges in 2022, but hopefully the industry can find creative ways to be more efficient and alleviate some of the logistical constraints we’re all facing.”